I spend a lot of time in conversations that start something like this:

“I’m really sorry I can’t fill in that report, it’s not accessible to me. Can you send it in another format?”

I then often have to explain why it’s not accessible. And then, how to make it accessible. This takes up a lot of my time.

I’m a product manager and an expert in benefits management. I’m also a neurodiverse woman living with visible and hidden disabilities.

At work, I have professional skills I use daily. Unfortunately, I don’t get to use them 100% of the time. People don’t always choose to make things accessible to people like me.

As a public sector organisation, we have a legal obligation to ensure our websites and mobile apps are accessible. We have the same obligation to our staff for internal documents and systems. And yet, both our external content and internal tools and templates don’t work for everyone.

I’d like to illustrate what this means in practice for someone with accessibility needs. I’m going to explain a little about some of my own daily experiences.

Accessibility is a choice, sometimes an unconscious one. We choose how to communicate.

My experiences

I use a few different assistive technologies at work. This includes speech recognition software and a screen reader. To help with my dyslexia, I change the contrast and screen colour on my monitor. I also have a personal assistant, who helps me with the more overwhelming and inaccessible documents and systems.

These tools and techniques allow me to interact with content in a way that meets my unique needs.

Here are some recurring formats I find problematic.

PDFs

Many people like to create and publish PDFs. PDFs give authors control over the layout and design of the document. They also lock the content so it cannot be changed. People also often assert that their users prefer PDFs.

However, locking content into a PDF takes away my control to customise it to my requirements. I can’t change the colour or text size. My screen reader doesn’t always read them properly. Navigating them with my voice is sometimes impossible.

Some may argue that you can make PDFs accessible by including tags, headings and alternative text (alt-text). However, it takes time and specialist skills to do this properly, and it’s more difficult to go back and make changes compared to other formats like HTML.

Even when made properly, the lack of flexibility means accessible PDFs still cannot meet everyone’s access needs. This includes people who don’t use assistive technology. Many people are now looking at content on a mobile screen. They are also likely to find PDFs harder to use.

Publishing content in HTML is far better for everyone. Easier to create, easier to change, easier to navigate.

PowerPoints

One problem with PowerPoint is that it doesn’t directly support Dragon Naturally Speaking. That’s the speech recognition software I use. It’s a very popular option for many people who use their voice instead of clicking or typing. Screen readers also struggle with PowerPoint.

PowerPoint is designed to be used as a visual aid for presentations. Unfortunately, it is often used for many other purposes.

This is an example of a report template I’ve been asked to use in the past. For some reason, teams often fixate on 1-page or 1-slide summaries of activity and use PowerPoint for this.

Perhaps the restricted format forces people to focus on the most important information. In reality, we just make the font smaller to squash in more information.

It’s not just me who has problems reading and understanding these summaries when too much information is presented at once. The layout can be confusing for many neurodiverse people and those with learning differences. Visually impaired people may also find it difficult.

If you need to create and share reports and other documents, Microsoft Word is a good alternative. Word documents encourage us to tell a linear story: we start at the top and read to the bottom. Word has excellent accessibility and there is even a built-in screen reader.

And if you are publishing content on a website, it should be in HTML wherever possible, instead of a document you have to download.

Graphics and images

There are lots of reasons why we use images: they can add context or add visual interest to a page. Using alt-text, we can usually explain the image for people using screen readers. Where possible, we should not put images of text (unless it is a logo). If we need images of text, the text should be included in the alt-text.

Problems start when complex images are used to explain detailed information. Diagrams, flowcharts and infographics are great tools. They are useful for people who can take in information in those formats. However, more effort needs to be made to give alternative, accessible formats.

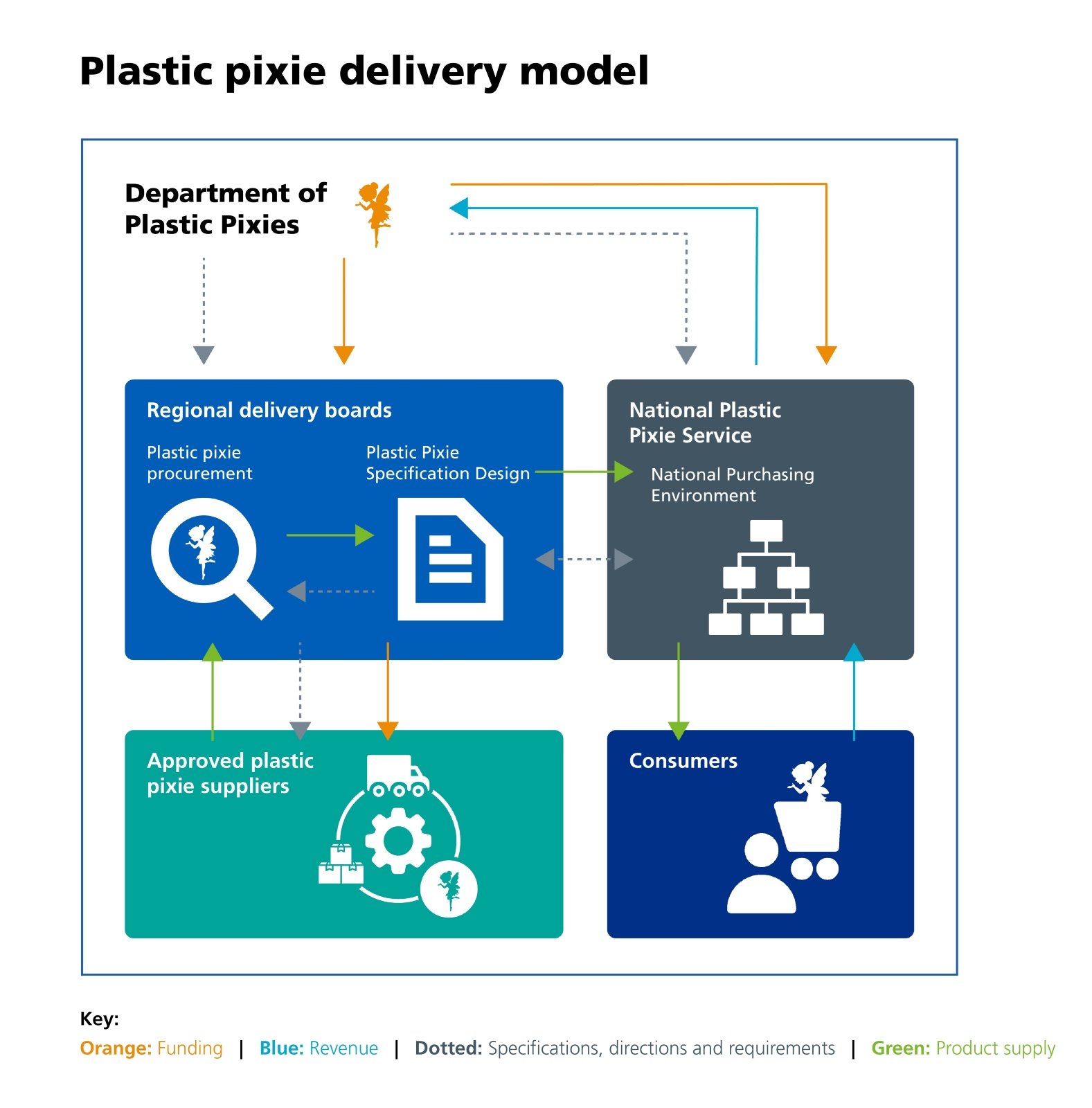

Take the following fictional example of the Department of Plastic Pixie delivery model. You might think it’s silly! However, it is inspired by real diagrams that are created within our organisation.

Can you make sense of this image?

It’s difficult to interpret even for people without accessibility needs. It’s impossible for those relying on screen readers. Also, some people with visual impairments will not be able to differentiate the different coloured lines – colour alone shouldn’t be used to convey information.

Only use images as visual aids and only with a full written explanation of what it is showing. This could be in the body copy or a link to a separate document. GOV.UK has some useful guidance about making images accessible.

It takes effort to make complex images accessible, but when you do, everyone benefits.

If we could spend 100% of our time on our work, just imagine how much that would improve our services to the public.

Choose to be accessible

Accessibility is a choice, sometimes an unconscious one. We choose how to communicate. But every accessibility issue in this blog is the result of a choice someone made.

I am pleased today that the team I work in has chosen to prioritise accessibility. That is making a difference to my working life. To us, professionalism includes clear and inclusive communication. We want to make tools and content that are useable by everyone.

I want my organisation – and others – to share our commitment to accessibility and inclusion. Ultimately, NHS England solves problems to improve health and care for everyone. People with accessibility needs have lots of skills to contribute. If we could spend 100% of our time on our work, just imagine how much that would improve our services to the public.

Related subjects

Share this page

Author

Latest blogs

Last edited: 15 May 2024 4:43 pm

Source: digital.nhs.uk

Please wait...

Please wait...

Add comment