It is pretty obvious to say that design changes people’s lives. If it didn’t, we wouldn’t spend so much of our time trying to get it right.

But the reality beneath that unoriginal claim struck home for me recently as I worked on a report tool, part of the replacement system for national cervical screening.

It’s not the most dramatic or heart-rending example of our impact – but is perhaps no less meaningful for that. It’s a small piece of work that speaks to the everyday reality we try to grapple with as interaction designers in the NHS.

Tosin Balogun at our Leeds office.

A beast

The cervical screening system used by clinical administrators to produce reports on smear testing was known to be a bit of a beast.

It had been in use since the 1990s and was beginning to show its age, so a replacement platform was commissioned.

The reporting tool – part of the cervical screening system – was notorious for being inconsistent and difficult to use. Research told us that users often struggled to produce reports and were sometimes unable to produce anything at all.

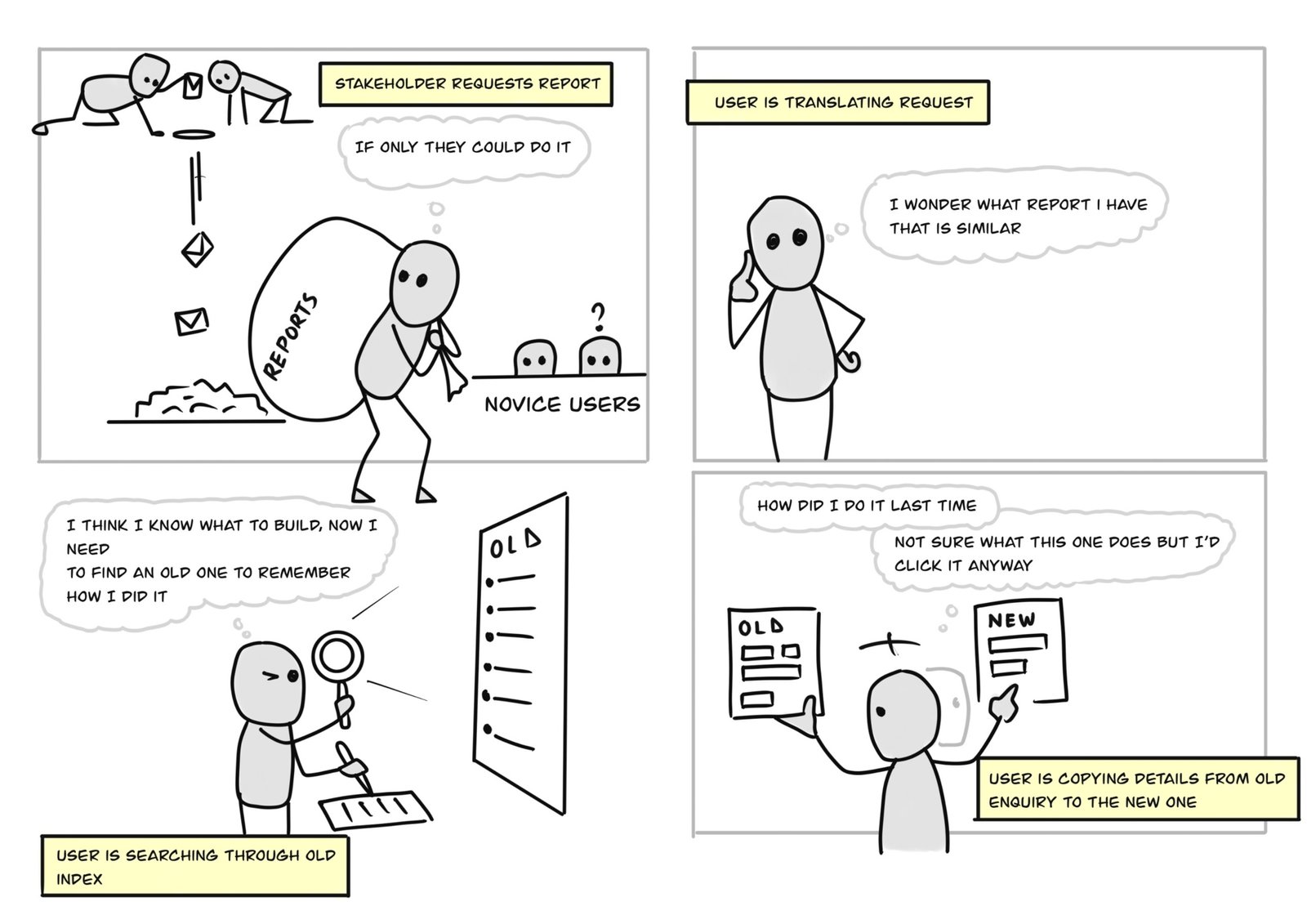

Once they found the fields that provided what they needed, they reused them to produce other related enquiries. This is because they knew it would produce something similar that would be useful.

Clinical administrators told us how “demanding on the brain” and exhausting it was to create something that was accurate and useful.

That one person’s reality, alone, was intensely motivating as we tried to improve the tool.

The tool never informed the user if they were adding the right or wrong data. Interaction therefore resulted in a lot of trial and error in the way they used it. For instance, the users had to tumble through many mistakes to figure out what each field did. The clinical administrators knew what they wanted to ask but the issue was getting the answer. This then meant they spent more time cross checking the report to ensure it was accurate.

In fact, its bad design was shaping not only their behaviour but their lives. One administrator confided that they waited till after office hours to begin making their reports. Think about that. That one person’s reality, alone, was intensely motivating as we tried to improve the tool.

Another administrator said they had developed a way around making reports by reusing details from old reports they had made – having to avoid the pain of making one from scratch. To do so, they had to scroll through a long list to find the one they needed. This was itself a time-consuming task.

The tool was resource intensive and if they ran it during business hours, all systems would become slow. Just a few people ended up using it so they became the ‘experts’ and they would have to set aside time from their busy day so as not to affect other clinical administrators’ work.

A simple step

But that insight gave us an immediate way to improve things.

One example was to add a search function to make it easier to find old reports by typing the name.

When we tried to validate this new approach with the users, however, we hit a snag. It seemed they didn’t know how to interact with it. They struggled with finding the right search terms because there wasn’t a consistency with how the reports were named. This meant they weren’t always certain what term to insert in order to come up with the right report they were looking for.

They came to realise that they needed a standard naming convention in order for the search function to operate more efficiently.

We wanted to wean them away from scrolling through many reports and transition them to using the search function that would ultimately make their life easier. This worked well when we tested it with the users.

A simple lesson

Even though I felt I understood the problem the users faced – and which solution would best solve their problem – the eventual design responded to their actual use of the tool. As Tero Väänänen, Head of Design at NHS Digital, explains in his blog What is your problem?, it is important to define the problems we are addressing before trying to solve them.

We can ensure we are affecting others positively by making conscious decisions rooted in rich research. Conscious design decisions rely on:

- getting a good understanding of what the problem is

- getting a good understanding of who our solution is for, their needs, behaviour, and environment

- making solutions that are validated with the people they are meant for

If we can make our systems a little less “demanding on the brain”, a little less destructive of people’s work-life balance, we will make the NHS a better place to work and perhaps we will also help people in the health care system develop a better understanding of the services they are offering to patients.

Share this page

Author

Latest blogs

Last edited: 25 July 2022 1:12 pm

Source: digital.nhs.uk

Please wait...

Please wait...

Add comment